Andros, 09. – 17.04.2022

Although being the second-biggest Cycladic Island, Andros seems to be some kind of terra incognita. It is rarely visited by herpetologists and even in historical dimensions, it appears that Andros always was somehow hidden behind other prominent islands. Even Roscher’s “Detailed dictionary of Greek and Roman mythology“ merely lets us know that the “heros eponymous” of the island was a guy called Andros: He received the island as a gift and colonized it but, after an “indignation”, he left and founded Antandros in Anatolia.

However, it seems that the island and its inhabitants prospered offside the world affairs. The wealth of the island may also have benefited from climate: Andros has much more precipitation than other Aegean islands. It has rich vegetation and several brooks bearing water all year round. We were curious what could be found on the island. And we wanted to take pictures of Lacerta citrovittata, an endemic species of the central and northern Cyclades – enough reasons to dedicate a trip to Andros!

Arriving on Andros

After our arrival at Athens airport in the late afternoon we headed to Rafina, a small harbour where the ferries to Andros depart. The next morning, we entered a ferry and after a two hours ride, we arrived at Gavrio and headed to our accommodation in Chora at the eastside of Andros. Our first thoughts were “Wow! So lush and green!” Andros is really beautiful in spring with its calm countryside, small villages nestled on rocky slopes and valleys with old oak forests. The second thing we noticed was the fact that the island is packed with lizards: Podarcis erhardii is really omnipresent. Good preconditions for a trip!

The valleys south of Chora

We started exploring the valleys at Sineti and Ormos Korthiou – actually, we didn’t know any specific locations; our available information was based on three older papers by Beutler & Frör (1980), Broggi (1996) and Buttle (1997) – so we had to search at a venture. As mentioned, Podarcis erhardii was literally everywhere, but finding Lacerta citrovittata turned tricky: First, these lizards seem to be rather rare, second, they are very shy, and third, they tend to hide in dense vegetation. Not the best conditions for a lizard safari. Furthermore, a strong wind significantly reduced reptile activity. As substitute, we photographed some local flora.

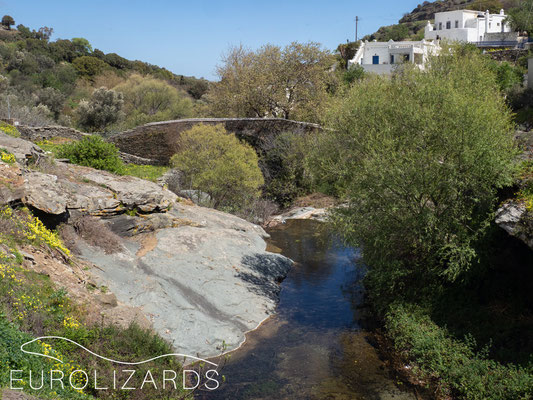

The valleys north of Chora

We gave it another try and explored the valleys around Stenies – lush landscapes, plenty of running water, ancient paths with drystone walls, olive groves and old platanus trees. An “Arcadian” landscape, and the perfect place for herping. This time, we had more luck with Lacerta citrovittata and came across some nice specimen, which were however, still difficult to photograph. Vipera ammodytes seems to be quite common in that area and we found some nice silver ones basking. These vipers rather look like the mainland subspecies meridionalis but not like the small Cycladic specimens which we had found on Naxos in 2016.

Coastal wetlands

There are several coastal sections with river mouths held back by sandy beaches and we were keen in exploring these promising habitats. But with regard to semi-aquatic herpetofauna, they turned less productive than we expected. One strange example is Pelophylax ridibundus: We assumed these frogs to be extremely abundant on such a humid island. Actually, Beutler & Frör mentioned in their paper that they didn’t record these frogs on Andros, whereas Broggi states that this species is “widespread and not rare”. However, we only saw very few specimen, in total less than 10. Without doubt, they should occur in some numbers, but they appeared more secretive than we expected. The other amphibian on the island is Bufo bufo, which we didn’t see, and we only found one juvenile Natrix natrix. On Andros, these snakes are listed as intermediate of subsp. persa and subsp. schweizeri. Indeed, they show a beautiful schweizeri pattern with dark blotches.

Another try for lemon stripes

We started another effort for citrovittata – and it was quite rewarding. We managed to take some acceptable shots of these big lizards. On Andros, males and females show prominent “lemon stripes” on pale bodies and the males show light bluish head coloration. Strange lizards, different from all other members of the genus Lacerta. Again, we came across some Vipera ammodytes and also found another juvenile Natrix natrix as well as Dolichophis caspius. The latter species seems to be widespread on Andros, as we saw several specimen dead on road.

Notes on Podarcis erhardii on Andros

Podarcis erhardii from Andros has been referred to subsp. mykonensis and without doubt, these lizards belong to the central / northern Cyclades group. However, the Andros Wall Lizards show a remarkable variability in color and pattern. Compared to this, most specimen of Podarcis erhardii on Mykonos or Tinos look very similar, as far as we know.

The basic type on Andros is a typical “mykonensis” morph with green backs and whitish underside. However, there are numerous exceptions: roughly estimated 5% of males have a red instead of white underside. Some males may show brown or bluish flanks. Furthermore, the extend and pattern of the dark reticulation may extremely vary between individual specimens.

The pictures below give an impression about this variability, which could be an indication for genetic diversity within the Andros population. One reason for this might be that the distance between Andros and neighboring Evia is less than 12 km. On Evia, the continental subsp. Podarcis erhardii livadiacus occurs. Although both islands are separated by 400 m water depth (Steno Kafirea), some introgression from Evia to Andros cannot be excluded. However, this seems rather unlikely.

Another possible reason for the high variability could be the geographic situation on Andros: The island is structured by four mountain ranges with deep valleys in between. This may have led to isolated populations during former periods with different climate or sea level.

With regard to behavior, it is remarkable that Podarcis erhardii can frequently be seen in pairs as the pictures in this report illustrate. Similar to our observations on Serifos, it seems that these lizards tend to strong pair behavior, particularly in areas with high population density – possibly an evolutionary strategy to reduce female's stress caused by mating efforts of other males (see our article on pair behavior of small Lacertids).

Epilogue: Attica herping

In the end of our trip, the ferry brought us back to Rafina in the afternoon. We still had some hours left for herping in adjoining Attica as our return flight was scheduled for the next morning. We didn’t have any specific locations but hoped to find Podarcis erhardii livadiacus – which sounds easier as it actually can be: This species is quite rare in Attica, only few mountain populations are known. Unexpectedly, this “herping blind date” was quite rewarding – we found seven species in some three hours. Finally, we even managed to encounter at least one single specimen of Podarcis erhardii livadiacus. A great farewell!

Literature

Broggi, M. F. (1996) - Die Feuchtgebiete der Insel Andros mit ihren Amphibien und hydrophilen Reptilien (Amphibia, Reptilia; Kykladen, Griechenland). – Herpetozoa – 8_3_4: 135 - 144.

Buttle, D. (1997) - Observations on reptiles and amphibians of Andros (Cyclades, Greece). - Brit. Herp. Soc. Bull., 60: 5-12.

Beutler, A. & Frör, E. (1980) - Die Amphibien und Reptilien der Nordkykladen (Griechenland). - Mitteilungen Zoologische Gesellschaft Braunau, 3 (10/12): 255-290.

EUROLIZARDS - The Home of European Lizards! © Birgit & Peter Oefinger